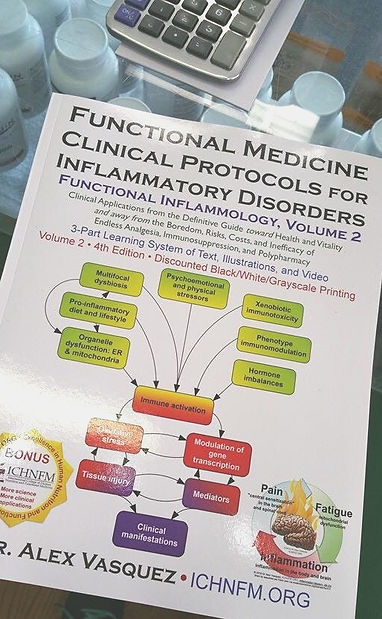

Inflammation Mastery, 4th Edition = 1200 pages + 30h video: Efficient and Effective Treatment of a Wide Range of Common Diseases based on DrV's Functional Inflammology Protocol (video) and Expert-level medical-clinical integration (video).

Now available from: BookDepository.com: free delivery worldwide; Amazon.com: paper and digital ebooks; Barnes and Noble.com: best prices paper/digital; ThriftBooks; AbeBooks; BetterWorldBooks; WaterStonesBooks

Bulk discounts are still available for student groups / required textbook shipped to the same address; contact admin@ichnfm.org for details and qualifications

See DrV's new Newsletter, Videos, Courses, and Blog: https://healthythinking.substack.com/p/selfpaced-learning-antiviral-nutrition

Multifocal Polydysbiosis: Dr Vasquez's concept of clinically important microbial imbalances in several locations, which combine to produce dysbiotic synergy in the development and maintenance of human disease

Multifocal Dysbiosis: Pathophysiology, Relevance for Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases, and Treatment With Nutritional and Botanical Interventions

This article was originally published

in paper and online in

Naturopathy Digest 2006 June;

reprinted here with permission of author

Dr Alex Vasquez

Introduction

In my last article, I surveyed and summarized "Dietary, Nutritional and Botanical Interventions to Reduce Pain and Inflammation."1 Although some doctors are familiar with what I meant when I wrote, "When pain and inflammation particularly are severe or recalcitrant, we need to consider that the inflammation might be being triggered by an occult or ‘silent' infection," I understand that this topic is sufficiently large and complex to warrant explication and elaboration for clinicians not up to date with the concept of multifocal dysbiosis and its relevance in allergic, inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.

Historical Context

Although the concepts of dysbiosis and "autointoxication" have existed for at least 100 years (Metchnikoff, 1903) and have consistently been embraced by the naturopathic profession, "dysbiosis" as a term in the allopathic medical literature lay dormant until it was finally resurrected in 1985 by Bai.2 Conversely, "autointoxication" has waxed and waned in the medical literature for decades3,4 but has mostly been ignored and denigrated, even though variants of this same problem are universally accepted by all health care professions under the names of "bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome,"5 "intestinal arthritis-dermatitis syndrome"6 and "D-lactic acidosis."7 Although Shakespeare reminded us nearly 300 years ago, "that which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet," health care professionals continue to bicker over the appropriate name(s) for dysbiosis, while patients with this problem continue to suffer and go largely untreated. Given the importance of these concepts in the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, I recently reviewed the literature in an article published by the American Chiropractic Association Council on Nutrition's journal, Nutritional Perspectives (available online8). What follows here is derived from that article, as well as more detailed work that I published in Integrative Rheumatology.9

Estimated Prevalence of Affected Populations

At least 70 percent of patients with chronic arthritis are carriers of "silent infections," according to a 1992 article published in the peer-reviewed medical journal Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.10 A 2001 article in that same journal which focused exclusively on five bacteria showed that 56 percent of patients with idiopathic inflammatory arthritis had gastrointestinal or genitourinary dysbiosis.11 Indeed, published research strongly and consistently indicates that bacteria, yeast/fungi, amoebas, protozoa, and other "parasites" (rarely including helminths/worms) are underappreciated causes of neuromusculoskeletal inflammation. In my own clinical practice, gastrointestinal dysbiosis is so common in patients with autoimmune/inflammatory disorders that I consider all of these patients to have dysbiosis until proven otherwise. We perform stool testing with a specialty laboratory, and I am rarely "disappointed" with the finding of normal stool analysis and parasitology. Overall, including patients without autoimmune/inflammatory disorders, I estimate that in my practice, approximately 80 percent of stool and parasitology examinations return with at least one clinically relevant abnormality that, when corrected, provides either subjective or objective improvement in the patient's primary complaint. My experience is consistent with that of other authors and researchers, who note a prevalence of dysbiosis in the range of 70 percent to 100 percent in patients with inflammatory disorders.9

Dysbiosis and Multifocal Dysbiosis

Recognizing the need to appreciate and transcend the contributions by Koch and Pasture, I've defined dysbiosis as "a relationship of non-acute non-infectious host-microorganism interaction that adversely affects the human host."9 When used without additional specification, the term "dysbiosis" generally is meant to imply "gastrointestinal dysbiosis." However, as research has continued to progress in this arena, clinicians are now obligated to appreciate the concept of "multifocal dysbiosis" because patients might have dysbiosis in extra-intestinal sites, namely their skin, mouth, sinuses, respiratory tract, genitourinary tract, surrounding environment, and parenchymal tissues. We might reasonably describe multifocal dysbiosis as "a clinical condition characterized by a patient's simultaneously having more than one foci/location of dysbiosis; generally the adverse physiologic and clinical consequences are additive and synergistic." Although different foci of dysbiosis generally require different types of treatment (e.g., oral versus topical versus environmental), the pathophysiologic mechanisms and clinical consequences are largely identical. Thus, sinorespiratory dysbiosis or genitourinary dysbiosis can be just as devastating as gastrointestinal dysbiosis, and therefore requires appropriate clinical consideration, particularly in patients with autoimmune/inflammatory disorders such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, polymyositis, ankylosing spondylitis, and various types of vasculitis.

Pathophysiology of Dysbiosis

I have identified at least 17 mechanisms by which microorganisms can cause immune dysfunction that promotes musculoskeletal inflammation. Each of the following exemplifies a mechanism by which microbes can cause "disease" without causing an "infection." Mechanisms by which microorganisms can contribute to musculoskeletal inflammation without causing "infection" include but are not limited to the following: molecular mimicry; superantigens; enhanced processing of autoantigens; bystander activation, peptidoglycans, teichoic acid, and exotoxins from gram-positive bacteria; endotoxins (lipopolysaccharide) from gram-negative bacteria; immunostimulation by bacterial DNA; activation of Toll-like receptors and NF-kappaB; immune complex formation and deposition due to the activation of B-lymphocytes/plasma cells; haptenization; damage to the intestinal mucosa; inhibition of detoxification; antimetabolites; autointoxication," "hepatic encephalopathy" and "intestinal arthritis-dermatitis syndrome;" impairment of mucosal and systemic defenses; impairment of mucosal digestion by microbial proteases and inflammation; and inflammation-induced endocrine dysfunction.

Nutritional and Botanical Approaches to Alleviating Dysbiosis-Induced Inflammation/Autoimmunity

The following concepts and therapeutics are particularly, though not exclusively, relevant for the treatment of gastrointestinal dysbiosis:

-

Diet modifications: The diet plan should ensure avoidance of sugar, grains, soluble fiber, gums, prebiotics, and dairy products, since these contain fermentable carbohydrates that promote overgrowth of bacteria and other microorganisms in the gut. Short-term fasting starves intestinal microbes, temporarily eliminates dietary antigens, alleviates "autointoxication," and stimulates the humoral immune system in the gut to more effectively destroy local microbes.12,13 Thus, implementation of the "specific carbohydrate diet" popularized by Gottschall14 along with periodic fasting, which has obvious anti-inflammatory benefits,15 can be used therapeutically in patients with conditions associated with dysbiosis-induced inflammation. Plant-based low-carbohydrate diets can lead to favorable changes in the quality and quantity of intestinal microflora. Hypoallergenic diets are proven beneficial for the treatment of the immune complex disease called mixed cryoglobulinemia.16,17

-

Antimicrobial treatments ("poison the microbes, not the patient"): Antimicrobial herbs can be used which directly kill or strongly inhibit the intestinal microbes. The most commonly used and well-documented botanicals in this regard are listed in the section below. Antimicrobial treatment frequently is continued for one to three months, and co-administration of drugs can be utilized when appropriate. Sometimes antimicrobial drugs are necessary, especially for acute and severe infections; often nutritional and botanical interventions are safer and more effective. Although these herbs generally are taken orally, some of them also can be applied topically (in a cream or lotion), and nasally (in a saline water lavage). Botanical medicines generally are used in combination, and lower doses of each can be used when in combination compared to the doses that are necessary when the herbs are used in isolation. When provided, dosage recommendations are intended for otherwise healthy adults; lower doses might be appropriate for children, the elderly and patients with renal or hepatic insufficiency.

-

Oregano oil in an emulsified, time-released tablet: Botanical oils that are not emulsified do not attain maximal dispersion in the gastrointestinal tract; products that are not time-released might be absorbed before reaching the colon in sufficient concentrations. Emulsified oil of oregano in a time-released tablet is proven effective in the eradication of harmful gastrointestinal microbes, including Blastocystis hominis, Entamoeba hartmanni, and Endolimax nana.18 An in vitro study19 and clinical experience support the use of emulsified oregano against Candida albicans. The common dose is 600 mg per day in divided doses (e.g., 150 mg four times per day) for at least six weeks.2

-

Berberine: Berberine is an alkaloid extracted from plants such as Berberis vulgaris and Hydrastis canadensis, and it shows effectiveness against Giardia, Candida, and Streptococcus, in addition to its direct anti-inflammatory and antidiarrheal actions. An oral dose of 400 mg per day is common for adults.21

-

Artemisia annua: Artemisinin has been used safely for centuries in Asia for the treatment of malaria,22,23 and it also has effectiveness against anaerobic bacteria, due to the pro-oxidative sesquiterpene endoperoxide. In a recent study treating patients with malaria, "The adult artemisinin dose was 500 mg; children aged < 15 years received 10 mg/kg per dose" and thus the dose for an 80-lb child would be 363 mg per day by these criteria.24 I commonly use artemisinin at 100 mg twice per day (with other antimicrobial botanicals such as berberine) in divided doses for adults with dysbiosis. One of the additional benefits of artemisinin is its systemic bioavailability.

-

St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum): Best known for its antidepressant action, hyperforin fromHypericum perforatum also shows impressive antibacterial action, particularly against gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus agalactiae. According to in vitro studies, the lowest effective hyperforin concentration is 0.1 mcg/mL against Corynebacterium diphtheriae with increasing effectiveness against multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus at higher concentrations of 100 mcg/mL.25 Since oral dosing with hyperforin can result in serum levels of 500 nanogram /mL (equivalent to 0.5 microgram/mL) it's possible that high-dose hyperforin will have systemic antibacterial action. Regardless of its possible systemic antibacterial effectiveness, hyperforin clearly should have antibacterial action when applied "topically," such as when it's taken orally against gastric and upper intestinal colonization. Extracts from St. John's Wort hold particular promise against multidrug-resistantStaphylococcus aureus26 and perhaps Helicobacter pylori.27

-

Myrrh (Commiphora molmol): Myrrh is remarkably effective against parasitic infections.28 A recent clinical trial against schistosomiasis showed "The parasitological cure rate after three months was 97.4 percent and 96.2 percent for S. haematobium and S. mansoni cases with the marvelous clinical cure without any side-effects."29

-

Bismuth: Bismuth commonly is used in the empiric treatment of diarrhea (e.g., "Pepto-Bismol") and commonly is combined with other antimicrobial agents to reduce drug resistance and increase antibiotic effectiveness.30

-

Peppermint (Mentha piperita): Peppermint shows antimicrobial and antispasmodic actions and has demonstrated clinical effectiveness in patients with bacterial overgrowth of the small bowel.

-

Uva ursi: Uva ursi can be used against gastrointestinal pathogens on a limited basis per culture and sensitivity findings; its primary historical and modern use is as a urinary antiseptic that is effective only when the urine pH is alkaline.31 Components of uva ursi potentiate antibiotics.32 This herb has some ocular and neurologic toxicity and should be used with professional supervision for low-dose and/or short-term administration only.33

-

Garlic: Garlic shows in vitro antimicrobial action against numerous microorganisms, including H. pylori, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Candida albicans, and this effect is mediated directly via microbicidal actions, as well as indirectly via dissolution of microbial biofilms34 and inhibition of quorum sensing.35However, since the antimicrobial components of garlic likely are absorbed in the upper gastrointestinal tract, I propose that it's unlikely that garlic can exert a clinically significant antidysbiotic effect in the lower small intestine and colon. In fact, two studies in humans have shown that despite its in vitro effectiveness against H. pylori, garlic is ineffective in the treatment of gastric H. pylori colonization.36,37 While these studies argue against the use of garlic as antimicrobial monotherapy, the possibility remains that garlic might enhance the clinical effectiveness of other antimicrobial therapeutics via its aforementioned ability to weaken microbial biofilms and to impair quorum sensing, which otherwise serve to protect yeast/bacteria from immune attack and from antibacterial/antifungal therapeutics.

-

Cranberry: Particularly effective for the prevention and adjunctive treatment of urinary tract infections, mostly by inhibiting adherence of E. coli to epithelial cells.38

-

Thyme (Thymus vulgaris): Thyme extracts have direct antimicrobial actions and also potentiate the effectiveness of tetracycline against drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.39 Thyme also appears effective against Aeromonas hydrophila.40

-

Clove (Syzygium species): Clove's eugenol has been shown in animal studies to have a potent antifungal effect.41

-

Anise: Although it has weak antibacterial action when used alone, anise does show in vitro activity against molds.42

-

Buchu/betulina: Buchu has a long history of use against urinary tract infections and systemic infections.43

-

Caprylic acid: Caprylic acid is a medium chain fatty acid that is commonly used in patients with dysbiosis, particularly that which has a fungal/yeast component. Beside empiric use, caprylic acid might be indicated by culture-sensitivity results provided with comprehensive parasitology.

-

Dill (Anethum graveolens): Dill shows activity against several types of mold and yeast.44

-

Brucea javanica: Extract from Brucea javanica fruit shows in vitro activity against Babesia gibsoni,Plasmodium falciparum,45 Entamoeba histolytica46 and Blastocystis hominis.47,48

-

Acacia catechu: Acacia catechu shows moderate in vitro activity against Salmonella typhi.49

-

Oral administration of proteolytic enzymes: The use of polyenzyme therapy in patients with dysbiotic inflammation is justified for at least four reasons. First, orally administered proteolytic enzymes are efficiently absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract into the systemic circulation50 to then provide a clinically significant anti-inflammatory benefit, as I reviewed recently.51 Second and more specifically, oral administration of proteolytic enzymes generally is believed to reduce the adverse effects of immune complexes,52 which play an important role in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, Sjogren's syndrome, and polyarteritis nodosa. Third, proteolytic enzymes have been shown to stimulate immune function53 and might thereby promote clearance of occult infections. Fourth, proteolytic enzymes inhibit formation of microbial biofilms and increase immune penetration and the effectiveness of antimicrobial therapeutics.54 Although individual enzymes might be used in isolation, enzyme therapy generally is delivered in the form of polyenzyme preparations containing pancreatin, bromelain, papain, amylase, lipase, trypsin and alpha-chymotrypsin.

-

Probiotic supplementation ("crowd out the bad with the good"): For most patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary dysbiosis, supplementation with Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus, and perhaps Saccharomyces and other beneficial strains is essential. The wide-ranging and well-documented benefits seen with probiotic supplementation provide direct support for the importance of microbial balance in health and disease. Supplementation with probiotics (live bacteria) is the best option, however prebiotics (such as fructooligosaccarides), and synbiotics (probiotics + prebiotics) also might be used. Synbiotic supplementation has been shown to reduce endotoxinemia and clinical symptoms in 50 percent of patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy,55 and probiotic supplementation safely ameliorated the adverse effects of bacterial overgrowth in a clinical study of patients with renal failure.56

-

Immunonutrition: Obviously, the diet should be nutritious and free of sugars and other "junk foods" that promote inflammation and suppress immune function.57 Especially in patients with gastrointestinal dysbiosis, vitamin and mineral supplementation should be used to counteract the effects of malabsorption, maldigestion and hypermetabolism that accompany immune activation. Additionally, oral glutamine in doses of six grams, three times daily can help normalize intestinal permeability, enhance immune function, and improve clinical outcomes in severely ill patients. Zinc and vitamin A supplementation are each well known to support immune function against infection. Selenium has clinically important anti-inflammatory and antiviral actions. Vitamin D supplementation reduces inflammation, protects against autoimmunity, and promotes immunity against viral and bacterial infections.58 Supplementation with IgG from bovine colostrum also can provide benefit against chronic and acute infections. Extracts from bovine thymus are safe for clinical use in humans and have shown anti-infective and anti-inflammatory benefits in elderly patients,59 as well as antirheumatic/anti-inflammatory benefits in patients with autoimmune diseases;60,61,62 in an animal study of experimental dental disease, administration of thymus extract was shown to normalize immune function and reduce orodental dysbiosis.63

-

Hepatobiliary stimulation for IgA-complex removal: As I suggested recently,64 stimulation of bile flow with botanical medicines such as beets, ginger,65 curcumin/turmeric,66 Picrorhiza,67 milk thistle,68Andrographis paniculata,69 and Boerhaavia diffusa70 might exert an anti-rheumatic benefit via facilitation of hepatic clearance of IgA-containing immune complexes. Validation of this hypothesis requires a clinical trial with pre- and post-intervention measurement of serum immune complexes and other clinical indexes.

-

Ensure generous bowel movements and consider therapeutic purgatives (purge: to free from impurities): Dysbiotic patients should consume a low-fermentation, fiber-rich diet that allows for 1-2 very generous bowel movements per day. Patients with severe or recalcitrant gastrointestinal dysbiosis can start the day with a laxative dose of ascorbic acid (e.g., 20 grams with four 8-ounce cups of water) and should expect liquid diarrhea within 30-60 minutes. The goal here is purgative physical removal of enteric microbes; in high concentrations, ascorbic acid has a direct antibacterial effect. Magnesium in elemental doses of 500-1,500 mg also helps soften stool and promote laxation.

-

Closure

Regardless of whether we use the terms "occult infections," "silent infections," "autointoxication" or "dysbiosis," health care professionals of all disciplines should appreciate the following two facts: 1. The scientific basis for dysbiosis-induced disease is well-established and the molecular mechanisms have been sufficiently elucidated. 2. A clear majority of patients with autoimmune/inflammatory disorders experience significant clinical benefit from a comprehensive treatment protocol that addresses food allergies/intolerances, anti-inflammatory nutrition, xenobiotic immunotoxicity, orthoendocrinology, and eradication of multifocal dysbiosis.9 As the science of health care advances, we see more and more clearly through the façade of the simplistic pharmacocentric model that focuses on single drugs for single pathways, while ignoring the underlying causes of disease.71 The better we understand the complex, web-like interconnections of physiological factors72 that synergize to create the phenomena of inflammation and so-called "autoimmunity," the better we can appreciate the common-sense "treat the cause" approach employed by naturopathic physicians for the restoration of health.

Dr Vasquez introduces the CE/CME course "Human Microbiome and Dysbiosis in Clinical Disease" (Main page) (PDF syllabus)

In this course, which details the molecular basis and clinical management of dysbiosis-induced disease, Dr Vasquez walks participants through the most important considerations and concepts for the successful management of various forms of dysbiosis, differentiated by metabolic impact and inflammatory consequences, as well as clinical phenotypes and prototypes, so that clinicians can truly master the impact of microbial imbalances in clinical care. The accompanying (sold separately at discount price) printed clinical monograph provides an additional 14 hours of video access for additional insight and clinical application. For a conceptual review in print, see DrV's translational review published in 2015.

Support this work that benefits you. To bring you this work, our costs include websites, software, video hosting, press releases, massive amounts of faculty time for research, presentation, editing, curation, professional fees, certifications and accreditations...

1. Enjoy the work: Free journal articles, excerpts, social media updates, and blogs with clinical importance, low-cost ebooks for managing migraine, fibromyalgia, viral infections, mTOR, press releases

2. Benefit from the work: Enhance your practice and clinical success with masterpiece books and courses that do more than pay for themselves, excellent ROI (return on investment)

3. Support the work: Purchase an online course, ebook, monograph, textbook or donate via GoFundMe.

References

-

Vasquez A. Dietary, Nutritional and Botanical Interventions to Reduce Pain and Inflammation. March 2006, naturopathydigest.com and March 2006, nutritionalwellness.com.

-

Bai K. On the mechanism of cereobiogen readjustment to dysbiosis. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;181:169-70.

-

Snyder RG. The value of colonic irrigations in countering auto-intoxication of intestinal origin. Medical Clinics of North America 1939; May: 781-788

-

Person JR, Bernhard JD. Autointoxication revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(3):559-63.

-

Jorizzo JL, Apisarnthanarax P, Subrt P, et al. Bowel-bypass syndrome without bowel bypass. Bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Mar;143(3):457-61.

-

Stein HB, Schlappner OL, Boyko W, Gourlay RH, Reeve CE. The intestinal bypass: arthritis-dermatitis syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1981 May;24(5):684-90.

-

Vella A, Farrugia G. D-lactic acidosis: pathologic consequence of saprophytism. "D-Lactic acidosis is a potentially fatal clinical condition seen in patients with a short small intestine and an intact colon. Excessive production of D-lactate by abnormal bowel flora overwhelms normal metabolism of D-lactate and leads to an accumulation of this enantiomer in the blood." Mayo Clin Proc. 1998 May;73(5):451-6.

-

Vasquez A. Reducing Pain and Inflammation Naturally. Part 6: Nutritional and Botanical Treatments Against "Silent Infections" and Gastrointestinal Dysbiosis, Commonly Overlooked Causes of Neuromusculoskeletal Inflammation and Chronic Health Problems. Nutritional Perspectives 2006; January Click to view it online.

-

Vasquez A. Integrative Rheumatology, 2006. Click to view it online.

-

Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Clinically silent infections in patients with oligoarthritis: results of a prospective study. "At the time of initial evaluation, 57 (69%) of the patients with oligoarthritis and 4/20 (20%) of the control subjects were carriers of clinically silent infections." Ann Rheum Dis. 1992 Feb;51(2):253-8.

-

Fendler C, Laitko S, Sorensen H, Gripenberg-Lerche C, Groh A, Uksila J, Granfors K, Braun J, Sieper J. Frequency of triggering bacteria in patients with reactive arthritis and undifferentiated oligoarthritis and the relative importance of the tests used for diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001 Apr;60(4):337-43.

-

Trollmo C, Verdrengh M, Tarkowski A. Fasting enhances mucosal antigen specific B cell responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997 Feb;56(2):130-4.

-

Ramakrishnan T, Stokes P. Beneficial effects of fasting and low carbohydrate diet in D-lactic acidosis associated with short-bowel syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1985 May-Jun;9(3):361-3.

-

Gottschall E. Breaking the Vicious Cycle: Intestinal Health Through Diet. Kirkton Press; Rev Edition (August 1, 1994).

-

Muller H, de Toledo FW, Resch KL. Fasting followed by vegetarian diet in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. "The pooling of these studies showed a statistically and clinically significant beneficial long-term effect." Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30(1):1-10.

-

Ferri C, Pietrogrande M, Cecchetti R, et al. Low-antigen-content diet in the treatment of patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. "CONCLUSION: These data show that an LAC diet decreases the amount of circulating immune complexes in MC and can modify certain signs and symptoms of the disease." Am J Med. 1989 Nov;87(5):519-24.

-

Pietrogrande M, Cefalo A, Nicora F, Marchesini D. Dietetic treatment of essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Ric Clin Lab. 1986 Apr-Jun;16(2):413-6.

-

Force M, Sparks WS, Ronzio RA. Inhibition of enteric parasites by emulsified oil of oregano in vivo.Phytother Res. 2000 May;14(3):213-4.

-

Stiles JC, Sparks W, Ronzio RA. The inhibition of Candida albicans by oregano. J Applied Nutr1995;47:96-102.

-

Force M, Sparks WS, Ronzio RA. Inhibition of enteric parasites by emulsified oil of oregano in vivo.Phytother Res. 2000 May;14(3):213-4.

-

Berberine. Altern Med Rev. 2000 Apr;5(2):175-7.

-

Dien TK, de Vries PJ, Khanh NX, Koopmans R, Binh LN, Duc DD, Kager PA, van Boxtel CJ. Effect of food intake on pharmacokinetics of oral artemisinin in healthy Vietnamese subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997 May;41(5):1069-72.

-

Giao PT, Binh TQ, Kager PA, Long HP, Van Thang N, Van Nam N, de Vries PJ. Artemisinin for treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria: is there a place for monotherapy? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001 Dec;65(6):690-5.

-

Giao PT, Binh TQ, Kager PA, Long HP, Van Thang N, Van Nam N, de Vries PJ. Artemisinin for treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria: is there a place for monotherapy? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001 Dec;65(6):690-5. Click to view it online.

-

Schempp CM, Pelz K, Wittmer A, Schopf E, Simon JC. Antibacterial activity of hyperforin from St John's wort, against multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus and gram-positive bacteria. Lancet. 1999 Jun 19;353(9170):2129.

-

Gibbons S, Ohlendorf B, Johnsen I. The genus Hypericum--a valuable resource of anti-Staphylococcal leads. Fitoterapia. 2002 Jul;73(4):300-4.

-

Reichling J, Weseler A, Saller R. A current review of the antimicrobial activity of Hypericum perforatum "A butanol fraction of St. John's Wort revealed anti-Helicobacter pylori activity with MIC values ranging between 15.6 and 31.2 microg/ml." L. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2001 Jul;34 Suppl 1:S116-8.

-

El Baz MA, Morsy TA, El Bandary MM, Motawea SM. Clinical and parasitological studies on the efficacy of Mirazid in treatment of schistosomiasis haematobium in Tatoon, Etsa Center, El Fayoum Governorate. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2003 Dec;33(3):761-76.

-

Abo-Madyan AA, Morsy TA, Motawea SM. Efficacy of Myrrh in the treatment of schistosomiasis (haematobium and mansoni) in Ezbet El-Bakly, Tamyia Center, El-Fayoum Governorate, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2004 Aug;34(2):423-46.

-

Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Sherman PM, Hunt RH. Helicobacter pylori: new developments and treatments. CMAJ. 1997;156(11):1565-74. Click to download PDF.

-

Yarnell E. Botanical medicines for the urinary tract. World J Urol. 2002 Nov;20(5):285-93.

-

Shimizu M, Shiota S, Mizushima T, Ito H, Hatano T, Yoshida T, Tsuchiya T. Marked potentiation of activity of beta-lactams against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by corilagin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001 Nov;45(11):3198-201 Click to view it online.

-

Wang L, Del Priore LV. Bull's-eye maculopathy secondary to herbal toxicity from uva ursi. "A 56-year-old woman who ingested uva ursi for 3 years noted a decrease in visual acuity within the past year. Ocular examination including fluorescein angiography revealed a typical bull's-eye maculopathy bilaterally." Am J Ophthalmol. 2004 Jun;137(6):1135-7.

-

Perez-Giraldo C, Cruz-Villalon G, Sanchez-Silos R, Martinez-Rubio R, Blanco MT, Gomez-Garcia AC. In vitro activity of allicin against Staphylococcus epidermidis and influence of subinhibitory concentrations on biofilm formation. "Sub-MICs of allicin also diminished the biofilm formations by S. epidermidis." J Appl Microbiol. 2003;95(4):709-11.

-

Bjarnsholt T, Jensen PO, Rasmussen TB, Christophersen L, Calum H, Hentzer M, Hougen HP, Rygaard J, Moser C, Eberl L, Hoiby N, Givskov M. Garlic blocks quorum sensing and promotes rapid clearing of pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. "The results indicate that a QS-inhibitory extract of garlic renders P. aeruginosa sensitive to tobramycin, respiratory burst and phagocytosis by PMNs, as well as leading to an improved outcome of pulmonary infections." Microbiology. 2005 Dec;151(Pt 12):3873-80. The in vivo portion of this study was performed in animals, not humans.

-

Graham DY, Anderson SY, Lang T. Garlic or jalapeno peppers for treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. "This study did not support a role for either garlic or jalapenos in the treatment of H. pylori infection. Caution must be used when attempting to extrapolate data from in vitro studies to the in vivo condition." Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 May;94(5):1200-2.

-

McNulty CA, Wilson MP, Havinga W, Johnston B, O'Gara EA, Maslin DJ. A pilot study to determine the effectiveness of garlic oil capsules in the treatment of dyspeptic patients with Helicobacter pylori. "Five patients completed the study. There was no evidence of either eradication or suppression of H. pylori or symptom improvement whilst taking garlic oil." Helicobacter. 2001 Sep;6(3):249-53.

-

Lynch DM. Cranberry for prevention of urinary tract infections. Am Fam Physician. 2004 Dec 1;70(11):2175-7. Click to download PDF.

-

Fujita M, Shiota S, Kuroda T, Hatano T, Yoshida T, Mizushima T, Tsuchiya T. Remarkable synergies between baicalein and tetracycline, and baicalein and beta-lactams against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Immunol. 2005;49(4):391-6.

-

Fabio A, Corona A, Forte E, Quaglio P. Inhibitory activity of spices and essential oils on psychrotrophic bacteria. "...thyme essential oil showed the greatest inhibition against A. hydrophila." New Microbiol. 2003 Jan;26(1):115-20.

-

Chami N, Chami F, Bennis S, Trouillas J, Remmal A. Antifungal treatment with carvacrol and eugenol of oral candidiasis in immunosuppressed rats. Braz J Infect Dis. 2004 Jun;8(3):217-26. Click to download PDF.

-

Elgayyar M, Draughon FA, Golden DA, Mount JR. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils from plants against selected pathogenic and saprophytic microorganisms. "Anise oil was not particularly inhibitory to bacteria (inhibition zone, approximately 25 mm); however, anise oil was highly inhibitory to molds." J Food Prot. 2001 Jul;64(7):1019-24.

-

Simpson D. Buchu--South Africa's amazing herbal remedy. "Buchu preparations are now used as a diuretic and for a wide range of conditions including stomach aches, rheumatism, bladder and kidney infections and coughs and colds." Scott Med J 1998 Dec;43(6):189-91.

-

Jirovetz L, Buchbauer G, Stoyanova AS, Georgiev EV, Damianova ST. Composition, quality control, and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of long-time stored dill (Anethum graveolens L.) seeds from Bulgaria. "Antimicrobial testings showed high activity of the essential A. graveolens oil against the mold Aspergillus niger and the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans." J Agric Food Chem. 2003 Jun 18;51(13):3854-7.

-

Murnigsih T, Subeki, Matsuura H, et al. Evaluation of the inhibitory activities of the extracts of Indonesian traditional medicinal plants against Plasmodium falciparum and Babesia gibsoni. J Vet Med Sci. 2005 Aug;67(8):829-31.

-

Wright CW, O'Neill MJ, Phillipson JD, Warhurst DC. Use of microdilution to assess in vitro antiamoebic activities of Brucea javanica fruits, Simarouba amara stem, and a number of quassinoids. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988 Nov;32(11):1725-9.

-

Sawangjaroen N, Sawangjaroen K. The effects of extracts from anti-diarrheic Thai medicinal plants on the in vitro growth of the intestinal protozoa parasite: Blastocystis hominis. "Dichloromethane and methanol extracts from the Brucea javanica seed and a methanol extract from Quercus infectoria nut gall showed the highest activity." J Ethnopharmacol. 2005 Apr 8;98(1-2):67-72.

-

Yang LQ, Singh M, Yap EH, Ng GC, Xu HX, Sim KY. In vitro response of Blastocystis hominis against traditional Chinese medicine. "The crude extracts of Coptis chinensis (CC) and Brucea javanica (BJ) were found to be most active against B. hominis." J Ethnopharmacol. 1996 Dec;55(1):35-42.

-

Rani P, Khullar N. Antimicrobial evaluation of some medicinal plants for their anti-enteric potential against multi-drug resistant Salmonella typhi. "Moderate antimicrobial activity was shown by Picorhiza kurroa, Acacia catechu, ..." Phytother Res. 2004 Aug;18(8):670-3.

-

Liebow C, Rothman SS. Enteropancreatic Circulation of Digestive Enzymes. Science 1975; 189(4201): 472-474.

-

Vasquez A. Reducing pain and inflammation naturally - Part 3: Improving overall health while safely and effectively treating musculoskeletal pain. Nutritional Perspectives 2005; 28: 34-38, 40-42. Click to view it online.

-

Galebskaya LV, Ryumina EV, Niemerovsky VS, Matyukov AA. Human complement system state after wobenzyme intake. VESTNIK MOSKOVSKOGO UNIVERSITETA. KHIMIYA. 2000. Vol. 41, No. 6. Supplement. Pages 148-149.

-

Zavadova E, Desser L, Mohr T. Stimulation of reactive oxygen species production and cytotoxicity in human neutrophils in vitro and after oral administration of a polyenzyme preparation. Cancer Biother. 1995 Summer;10(2):147-52.

-

Tets VV, Knorring GIu, Artemenko NK, Zaslavskaia NV, Artemenko KL. [Impact of exogenic proteolytic enzymes on bacteria][Article in Russian] "The enzymes were shown to inhibit the biofilm formation. When applilied to the formed associations, the enzymes potentiated the effect of antibiotics on the bacteria located in them." Antibiot Khimioter. 2004;49(12):9-13.

-

Liu Q, Duan ZP, Ha da K, et al. Synbiotic modulation of gut flora: effect on minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2004 May;39(5):1441-9.

-

Simenhoff ML, Dunn SR, Zollner GP, Fitzpatrick ME, Emery SM, Sandine WE, Ayres JW. Biomodulation of the toxic and nutritional effects of small bowel bacterial overgrowth in end-stage kidney disease using freeze-dried Lactobacillus acidophilus. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1996;22(1-3):92-6.

-

Seaman DR. The diet-induced proinflammatory state: a cause of chronic pain and other degenerative diseases? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002 Mar-Apr;25(3):168-79. See also Vasquez A. Chiropractic and Naturopathic Medicine for the Promotion of Wellness and Alleviation of Pain and Inflammation.Click to view it online.

-

Vasquez A, Manso G, Cannell J. The clinical importance of vitamin D (cholecalciferol): a paradigm shift with implications for all healthcare providers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004 Sep-Oct;10(5):28-36.Click to view it online.

-

Pandolfi F, Quinti I, Montella F, Voci MC, Schipani A, Urasia G, Aiuti F. T-dependent immunity in aged humans. II. Clinical and immunological evaluation after three months of administering a thymic extract. Thymus. 1983 Apr;5(3-4):235-40.

-

Lavastida MT, Goldstein AL, Daniels JC. Thymosin administration in autoimmune disorders. Thymus. 1981 Feb;2(4-5):287-95.

-

Thrower PA, Doyle DV, Scott J, Huskisson EC. Thymopoietin in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1982 May;21(2):72-7.

-

Malaise MG, Hauwaert C, Franchimont P, et al. Treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with slow intravenous injections of thymopentin. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomised study. Lancet. 1985 Apr 13;1(8433):832-6.

-

Manti F, Kornman K, Goldschneider I. Effects of an immunomodulating agent on peripheral blood lymphocytes and subgingival microflora in ligature-induced periodontitis. Infect Immun. 1984 Jul;45(1):172-9.

-

Vasquez A. Do the Benefits of Botanical and Physiotherapeutic Hepatobiliary Stimulation Result From Enhanced Excretion of IgA Immune Complexes? Naturopathy Digest 2006; January.

-

Yamahara J, Miki K, Chisaka T, Sawada T, Fujimura H, Tomimatsu T, Nakano K, Nohara T. Cholagogic effect of ginger and its active constituents. "Further analyses for the active constituents of the acetone extracts through column chromatography indicated that [6]-gingerol and [10]-gingerol, which are the pungent principles, are mainly responsible for the cholagogic effect of ginger." J Ethnopharmacol. 1985;13(2):217-25.

-

Rasyid A, Lelo A. The effect of curcumin and placebo on human gall-bladder function: an ultrasound study. "On the basis of the present findings, it appears that curcumin induces contraction of the human gall-bladder." Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999 Feb;13(2):245-9.

-

Saraswat B, Visen PK, Patnaik GK, Dhawan BN. Anticholestatic effect of picroliv, active hepatoprotective principle of Picrorhiza kurrooa, against carbon tetrachloride induced cholestasis. "Significant anticholestatic activity was also observed against carbon tetrachloride induced cholestasis in conscious rat, anaesthetized guinea pig and cat. Picroliv was more active than the known hepatoprotective drug silymarin." Indian J Exp Biol. 1993 Apr;31(4):316-8.

-

Crocenzi FA, Sanchez Pozzi EJ, Pellegrino JM, Rodriguez Garay EA, Mottino AD, Roma MG. Preventive effect of silymarin against taurolithocholate-induced cholestasis in the rat. "We conclude that SIL counteracts TLC-induced cholestasis by preventing the impairment in both the BS-dependent and -independent fractions of the bile flow." Biochem Pharmacol. 2003 Jul 15;66(2):355-64.

-

Shukla B, Visen PK, Patnaik GK, Dhawan BN. Choleretic effect of andrographolide in rats and guinea pigs. "Andrographolide from the herb Andrographis paniculata (whole plant) per se produces a significant dose (1.5-12 mg/kg) dependent choleretic effect (4.8-73%) as evidenced by increase in bile flow, bile salt, and bile acids in conscious rats and anaesthetized guinea pigs." Planta Med. 1992 Apr;58(2):146-9.

-

Chandan BK, Sharma AK, Anand KK. Boerhaavia diffusa: a study of its hepatoprotective activity. "The extract also produced an increase in normal bile flow in rats suggesting a strong choleretic activity." J Ethnopharmacol. 1991 Mar;31(3):299-307.

-

Vasquez A. Twilight of the Idiopathic Era and the Dawn of New Possibilities in Health and Health Care.Naturopathy Digest 2006.

-

Vasquez A. Web-Like Interconnections of Physiological Factors. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician's Journal, 2006; April/May: 32-7. Reprinted from David Jones (ed). Textbook of Functional Medicine. Institute for Functional Medicine; Gig Harbor, WA: 2006.